Article by Klaus A. Wobbe, Founder & Managing Director of Intalcon

WHAT SFDR WAS MEANT TO ACHIEVE

The EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) was supposed to achieve three things: create transparency, curb greenwashing and steer capital flows into demonstrably sustainable activities. The EU has since admitted that this goal has only been partially achieved with the current design – and has therefore presented a revision (“SFDR 2.0”), which still has to pass through the legislative process [1].

Under the current rules, so-called “Article 8 funds” promote environmental and/or social characteristics and "Article 9 funds" set a sustainable investment objective. However, neither transparency nor disclosure category provides any guarantee of impact [2].

WHAT CHANGES WITH SFDR 2.0?

As an image, it’s easiest to picture three labels on the fund shop shelf:

- Sustainable: clear, measurable sustainability targets

- Transition: transition pathways with interim targets and evidence

- Other ESG: ESG risks considered, without promising impact

New is the integration of the term “impact”. The claim is protected and must be aligned in substance with intentionality, a theory of change, measurable results (KPIs) and clear disclosure. This addresses greenwashing but does not demand additionality.

The new categories explain funds better – but they still do not finance any additional wind farms or heat pumps. Impact only arises if (a) additional capital flows into the company’s coffers (primary market / new issuance) or (b) engagement demonstrably changes corporate decisions (e.g. CAPEX paths)[3].

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY MARKET

For those not yet familiar with the distinction: IPOs, capital increases, new bond issues etc. are handled on the primary market. This is where new money flows to the company or issuer.

In contrast, trading on stock exchanges between investors takes place on the secondary market [13]. Here only the owner of a share or financial instrument changes. In this trading, the listed company itself does not receive any capital. The misconception “Every share purchase finances the company” is persistent – but it is only true on the primary market.

Trading shares on the secondary-market works similar to any other secondary market. If you buy a new mobile phone from the manufacturer, the manufacturer receives the proceeds from the sale. But if you buy a used mobile phone from Ebay, the previous owner receives the proceeds from the sale. The manufacturer does not receive any further income from this sale; it is not even aware of it.

Here are two examples, representative of many equity funds, where no measurable, sustainable impact is generated in the sense described above:

- LU1966631001 (Carmignac Portfolio Grandchildren A, Article 9) is a global equity fund with an SRI (socially responsible investing) approach. It buys and sells shares of listed companies; transactions therefore take place on the secondary market. Result: no impact [4].

- LU1529808336 (JPMorgan Funds – Europe Sustainable Equity A (acc) EUR, Article 8) is a European equity fund that promotes sustainable characteristics. Again, trading on the exchange means secondary market – no fresh corporate capital from the purchase/sale of fund units. Result: no impact [5].

WHAT EQUITY FUNDS (MIGHT) ACHIEVE – AND WHERE THE LIMITS ARE

Three approaches are often mentioned, but their effectiveness is questionable:

- Engagement/stewardship: Influencing corporate practices, e.g. by exercising voting rights at annual general meetings, is effective if it actually changes decisions (CAPEX, business model change). However, the success of engagement is difficult to measure due to the time horizon and complexity involved, and even collaborative action often has only limited influence and may involve legal risks.

- Cost of capital/price effects: When demand for "bad" shares declines, the "bad" company has to offer more to the banks that are to place the new shares when raising capital. This makes it more expensive for the company to raise debt capital. This correlation is theoretically plausible, but empirically often insignificant and difficult to attribute.

- IPO / capital increase (primary market): When a company goes public for the first time (IPO) or issues new shares (capital increase), this takes place on the primary market. In this case, fresh money flows directly to the company. The company can use this capital to grow, develop new products or operate more sustainably. However, such investments are rarely made with the aim of achieving a positive impact; financial returns are usually the primary focus. According to recent studies, the proportion of actual impact investments in both Germany and globally is only around 1%.

Research shows that so far investors only generate impact in a few cases through their investments. For broadly diversified equity funds that simply hold the shares of many listed companies, a traceable impact usually remains an exception. [3][6].

DO DIVESTMENTS HAVE AN IMPACT?

Divestment – not investing in certain shares – is a socially and ethically motivated stance. In recent years, targets of divestment campaigns have included tobacco, weapons, adult entertainment and gambling.

Not investing in a share does not normally make the world a better place. On the secondary market, as stressed repeatedly, no new capital flows into the company when a position is sold, and the capital costs of the “excluded” firm only rise noticeably if very many investors avoid the same shares over a long period. That is rather unlikely [7].

Even the much-cited fossil fuel divestment movement has, according to Oxford analysis [14], only very limited direct financial effects. Its strongest lever is stigma – i.e. indirect political and reputational pressure – not an immediate halt in investment.

On a private level it looks similar: someone excludes Shell from their portfolio but still fills up the car at a Shell fuel station or tops up the oil tank for the winter. Consumption creates demand; the exclusion in the portfolio does not change that.

A small reality check for you as a reader: “Which three products made from oil derivatives are you holding right now – your phone? Your headphones? Your ballpoint pen?” Ask yourself: “What have I just consumed? (Fuel, flights, Amazon parcel?)” Consumption patterns alter emissions more than a portfolio exclusion does. If no oil is bought, none will be burned.

“I DON’T TAKE DIVIDENDS FROM ‘DIRTY’ COMPANIES”

I recently heard this sentence during a talk. I understand the impulse. But: whether you hold a share such as ExxonMobil or not does nothing to change Exxon’s profits – and therefore nothing to change the fact that dividends are paid. If you do not hold the stock, someone else collects the dividend. The secondary market reallocates ownership; it does not provide new financing to the company.

If I want impact, it is more meaningful to direct the proceeds – in this case dividends – into projects with demonstrable impact (for example via donations).

NEW EVIDENCE 2025: MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT THE CLIMATE IMPACT OF GREEN FUNDS

A new study (Dec. 2025, [10]) compares the assessments of 2,101 German retail investors and 182 academic experts on the climate impact of a typical green fund. The result: retail investors significantly overestimate the impact.

More than three-quarters of retail investors consider the impact “relevant”, while around 60% of experts disagree. Asked how much an investment of €10,000 over ten years “neutralises” of their personal CO₂ footprint, the median answer among retail investors is 10%; among experts it is 2%. The most common estimate among experts is 0% (no impact).

From a behavioural economics perspective this is relevant: when retail investors are shown the experts’ results, both their impact expectations and their willingness to pay decline. In the experiment, preference for the green fund falls from 61.75% to 55.50%; willingness to pay is significantly reduced (among other things from 61 to 47 basis points, i.e. from €6.11 to €4.67).

The qualitative analysis reveals the reason for the discrepancy: retail investors think more in terms of company impact (“the companies in the fund are green, therefore it has impact” → WRONG), while experts focus on investor impact and the transmission channels of financial markets (prices / cost of capital → investment decisions). Experts see more effective channels in voting-rights engagement and the direct financing of green companies that face financing constraints. A mere reallocation in the secondary market is viewed far more sceptically.

Interpretation: the findings support our thesis: without additionality (primary market) or demonstrably effective engagement, labelling and portfolio selection rarely generate impact. SFDR 2.0 sharpens categories and protects the term “impact” – but does not automatically solve the central problem of causality.

“Impact means: intentionality, causality, measurability - not just a label.”

The revision of SFDR links “impact” to intentionality, a theory of change, outcome measurement and name protection.

Excursus: Theory of Change (ToC)

A ToC describes in a forward-looking and causal way how activities lead from inputs → outputs → outcomes → impact – including assumptions and risks along the chain. It serves as a planning and evaluation framework that defines responsibilities, metrics and audit trails. Core elements are:

(i) context / problem analysis & target picture (“intended impact”),

(ii) causal chain and interim targets,

(iii) assumptions / risks,

(iv) measurement / evaluation design (KPIs) [8][9].

SHEER SCALE – AND WHAT IT COULD ACHIEVE

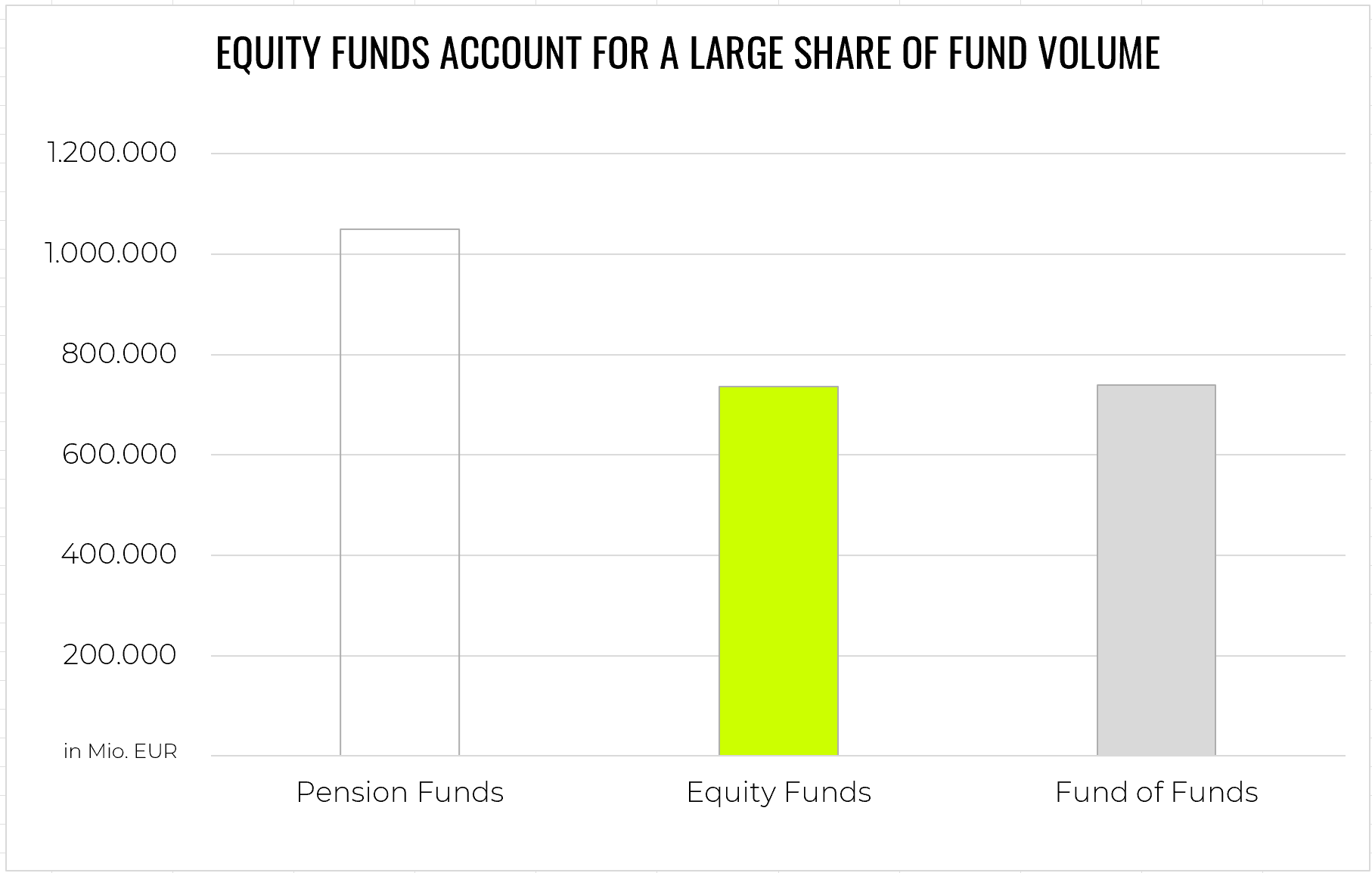

Equities account for a large share of the volume of both investment funds and stock exchange trading. But caution: Why do traditional equity funds rarely generate immediate impact? As already mentioned, they operate predominantly on the secondary market: investors buy shares from other investors.

Assets managed in Article 8 and Article 9 funds in the EU totalled around €6.4 trillion at the end of June 2025, representing roughly 59% of the entire EU fund market – with 56.3% in Article 8 funds and 2.9% in Article 9 funds. Conservatively estimated, more than €3 trillion of this is tied up in equity funds under Article 8/9 [11].

Thought experiment: if only 1% of this equity volume were channelled each year measurably into additional projects (primary market or a transparent return-impact mechanism), that would amount to more than €30 billion per year for real-world measures – starting today. Let us hope for regulatory adjustments that move in this direction.

INTERIM CONCLUSION

SFDR 2.0 rearranges the shelf and protects terminology – but without primary-market additionality or verifiably effective engagement it often remains feel-good rather than real-world impact, especially in the largest segment, equity funds – even after SFDR 2.0. That is a real pity.

A PRAGMATIC SOLUTION

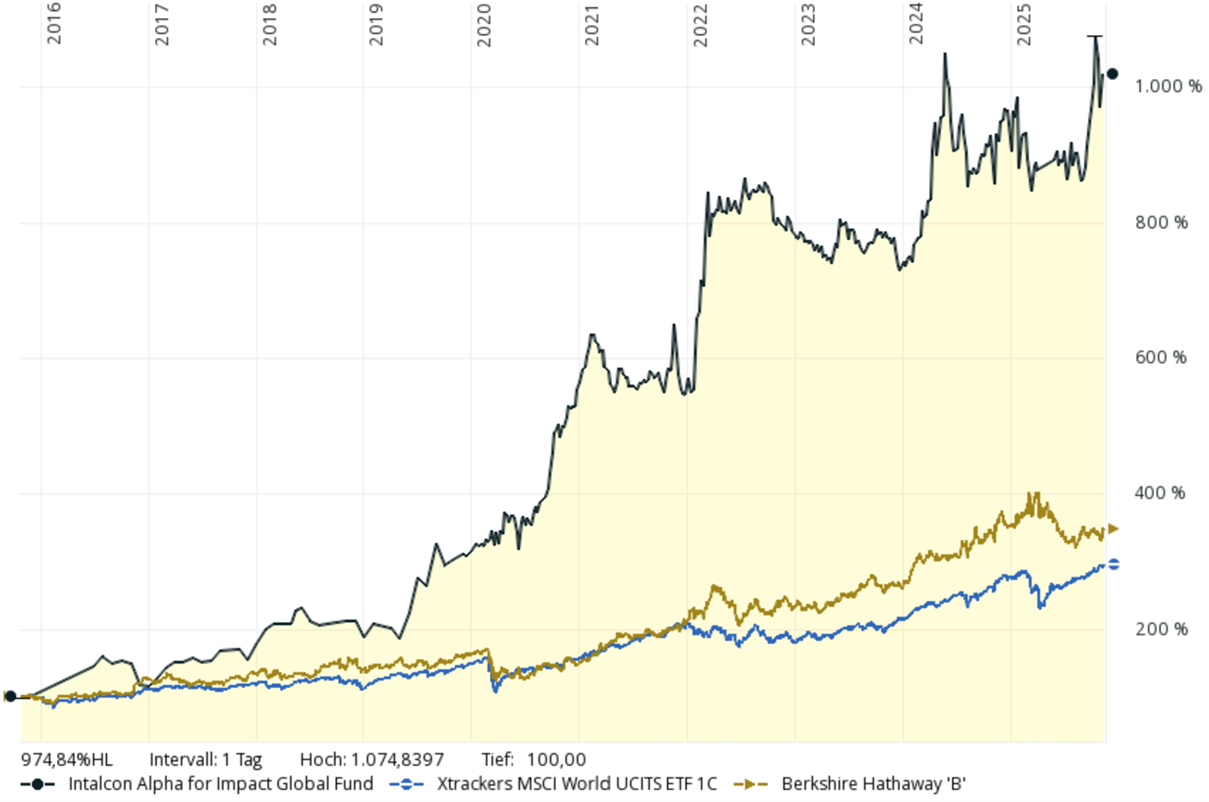

With the fund Intalcon Alpha for Impact Global, we link return directly to impact: 20% of the proceeds from management and performance fees are channelled through the Intalcon Foundation into projects aimed at restoring biodiversity, mitigating global warming and protecting the oceans. Impact is created in a planned and liquid way, regardless of whether the return was generated on the primary or secondary market.

For context: the fund has existed since 2011; over a ten-year period, it has clearly outperformed both the MSCI World and Berkshire Hathaway B – Warren Buffett’s stock [12]. This underlines that return and impact are not mutually exclusive when the mechanism is right. Past performance is, as we all know, is no guarantee of future returns – but here the mechanism is what matters.

WE FINALLY NEED TO CLEAR UP SOME MISCONCEPTIONS

- “Every time I buy a share, I finance the company."

No. On the secondary market, the buyer pays the previous owner, not the company. Direct financing only exists on the primary market (IPOs / capital increases / new issues). - “Article 9 = guaranteed impact.”

No. The current SFDR regulates disclosure and objectives, not the assurance of additional impact. Many supervisors are currently debating reforms, precisely because the labels are so often misunderstood. - “Green funds solve the big problems.”

Yes and no. Only if engagement measurably changes decisions or fresh capital flows additionally into effective projects. Otherwise it remains portfolio cosmetics. - “Divestments are the solution.”

No. In the end, what matters is not whether a fund contains nothing "bad” or whether the stocks in the fund have a good ESG rating – what counts is whether there is measurable improvement in the real world. And ultimately, divestments even shrink the investment universe and therefore also the return potential – the exact opposite of what we urgently need - capital to finance solutions that truly make the world a better place.

CONCLUSION

Anyone who wants demonstrable impact needs either primary-market financing (new capital with a clear impact intention) or measurable engagement that leads to concrete changes in decisions. For the latter, however, there is still a lack of successful examples.

When will we finally – as investors, foundations, family offices, asset managers and fund companies – commit to consistently linking every investment decision with additional positive impact? The instruments are already on the table. All that is missing is the will to use them.