Real progress is often difficult and has to be hard fought for. On the one hand, this is because simple problems have long been solved and only the complicated things remain. On the other hand, it is often the case that the answer to a question does not represent a satisfactory end result, but only produces new questions.

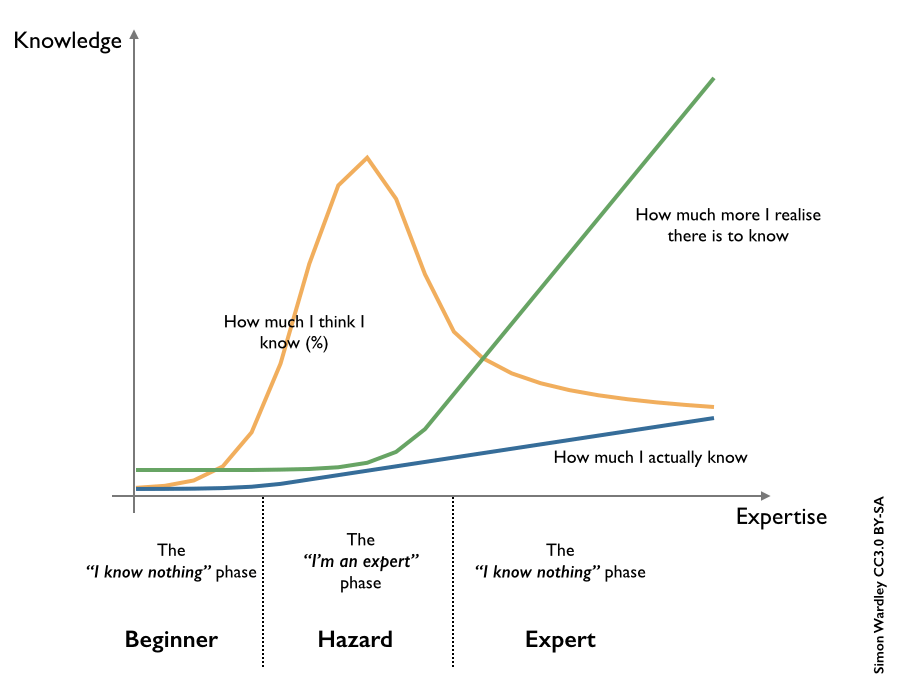

This can lead to a paradox in one's own perception: The more I know, the more I realise all the things I don't know - and how much more there is out there to find out. In a way, it's a luxury problem that only opens up when you're a real expert in a certain field and realise how little of "everything" you've actually understood in the first place.

This is the antithesis of the classic Dunning-Kruger effect. This describes that people with little experience in a field are not able to realise that they are actually incompetent. That is why they easily overestimate themselves. Real experts, on the other hand, who have already realised how little they actually know, often underestimate themselves. [2]

Source: Wardley, S. (2008), Three Stages of Expertise, http://blog.gardeviance.org

But that is not all. As far as the financial markets are concerned, there is something aggravating about everyday problems such as the appropriate allocation in the portfolio: things are constantly changing.

This in turn means that moving variables are being handled. Experts regularly have to put different things into context and interpret them on the basis of experience. Nevertheless, right and wrong are close together, because in the end much depends on a decisive factor that cannot always be grasped with logic: The way countless market participants react - rationally or irrationally - to certain events.

So there is a double problem: on the one hand, the events themselves are largely unpredictable, and on the other hand, so are the reactions to them. Against this background, it is ultimately only honest if even experienced market participants admit:

"I know that I know nothing..."

One could now argue that this perspective is incorrect. After all, there are countless analysts who continuously assess all kinds of securities on the basis of fundamental data and expectations based on them. Surely this should reflect genuine knowledge.

Fundamental problems

And it is true. These analyses lead to markets being quite efficient today. This requires a high level of detail in information that is available promptly and is continuously updated. In other words, there are permanently high information costs.

But even then it is impossible to understand all the details of, for example, a company in order to always make the best decision on the respective share based on this. This is because both the companies themselves and their economic environment are constantly changing. So the picture will never be perfectly resolved, a certain blurring remains even with the best snapshot.

Algorithmic advantages

This is where algorithmic models come into play. Instead of going into detail, information is usually aggregated here at the meta level as key figures for all values of the universe under consideration in order to make a rough preselection. Based on historical correlations and corresponding risk/reward estimates, a portfolio with the best setups, i.e. the highest statistical chances of success, can then be selected from the mass of individual stocks at the push of a button.

Many of the individual signals will not work, but that is taken into account. It is just a matter of having a small advantage and systematically playing it out until it crystallises over time from the countless trades. This is where the second part of the quant philosophy mentioned earlier comes in:

...And with that, I already know quite a lot.

Knowing what you don't know and focusing all resources on the part of the data from which added value can be generated is a great advantage. To ignore what a large part of the competition is struggling with on a daily basis. And to look for alternatives that can achieve the same goal in a completely different way.

Conclusion

Of course, it is not entirely true that quants assume they know nothing. But in terms of the idea, this philosophy fits quite well. Instead of arguing back and forth about how to interpret individual quarterly figures, decisions are made independently on a meta-level. Purely systematically, with a large portion of modesty and ideally with the corresponding emotional distance.

It is not uncommon for system traders who go long or short in a stock not to know at all what business the company is in, and perhaps they have never heard its name before. Most of the time it doesn't matter anyway. But what does matter is structured programming, clean backtests and fast algorithms. And in these areas, a good quant would probably never say, "I know I don't know anything."