When Your Only Escape Route Is Paying a Premium

Article by Michael Nicoletos, Founder & CEO at DeFi Advisors

The Narrative Everyone Believes

Gold has surged to $4,200 per ounce, and financial media has settled on a convenient explanation: the world is losing faith in the US dollar. Central banks are supposedly fleeing U.S Treasuries, seeking shelter in the ancient safety of gold. It’s a narrative that fits neatly into headlines about de-dollarization, BRICS currencies, and the decline of American financial hegemony.

There’s just one problem: this story fundamentally misreads what’s actually happening.

Yes, we’re witnessing global currency debasement. Your purchasing power is eroding whether you hold dollars, euros, or yuan. This can be seen in the US stock market and other asset classes, such as Bitcoin. The question isn’t whether fiat currencies are losing purchasing value (they are at a rate of 8-12% a year) but rather what this particular gold rush might be revealing about the world’s second-largest economy.

The uncomfortable truth is that China’s gold-buying frenzy isn’t a vote of no confidence in America. It’s a desperate hedge against something far more alarming: the potential implosion of China’s own economic system.

The Shanghai Premium: A Clue Everyone Misreads

Walk into any financial analysis of gold markets, and you’ll encounter the Shanghai premium: gold trades at higher prices on the Shanghai Exchange than on Chicago’s CME. Many analysts point to this spread as proof positive that China is positioning itself for a post-dollar world order.

But are they reading it correctly?

First, let’s establish the baseline facts. The United States holds 8,133 tons of gold reserves, the world’s largest hoard. China, even by the most generous estimates, could possess around 5,000 tons. These aren’t the numbers of a country engineering a currency revolution; they’re the numbers of a country whose citizens are paying premiums to escape something.

That something is China’s economic reality, and it’s far more precarious than most observers understand.

The Balloon That Won’t Inflate

Consider this economic puzzle: China has pumped an extraordinary amount of money into its economy, yet it hasn’t grown proportionately. It’s like filling a balloon with water when the balloon has multiple holes - no matter how much water you pour in, the leaks cap its true growth potential.

The numbers are staggering and paradoxical:

China’s Economic Profile:

- Official GDP 2024: $18.8 trillion

- Money Supply (M2)*: $47 trillion

- Total FX Reserves: $3.2 trillion (only $760 billion is liquid)

- Banking System Assets: $64 trillion (an astronomical 344% of GDP)

US Economic Profile:

- GDP 2024: $29 trillion

- Money Supply (M2)*: $21 trillion

- FX Reserves: Minimal (as the reserve currency issuer, the US doesn’t need them)

- Banking System Assets: $24 trillion (a comparatively modest 82% of GDP)

*M2 is a measure of the money supply that includes all of M1 (cash, traveler’s checks, and checking account deposits) plus savings deposits, small time deposits, and retail money market funds. It is a broader measure of the money supply than M1 because it includes assets that are liquid but not as immediately accessible as cash.

Here’s what should shock you: China has more than double the money supply of the United States. Yet its economy is only about two-thirds the size, and that’s assuming China’s official GDP figures are accurate, which we’ll soon see is questionable.

Let’s rewind to 2009-2010. Both countries had roughly $10 trillion in M2. Fast forward to today: America’s M2 has grown to $22.2 trillion, supporting a $29 trillion economy. China’s M2 has exploded to $47 trillion, yet its official GDP is just $18.8 trillion.

Where did all that money go? What happened to the economic growth that should have accompanied such massive monetary expansion?

The answer lies in understanding how China’s financial system fundamentally differs from market-based economies, and why Chinese citizens are willing to pay premiums for gold.

Why Chinese Citizens Are Fleeing to Gold

The Chinese aren’t buying gold because they fear the dollar. They’re buying gold because they understand two terrifying realities about their own system:

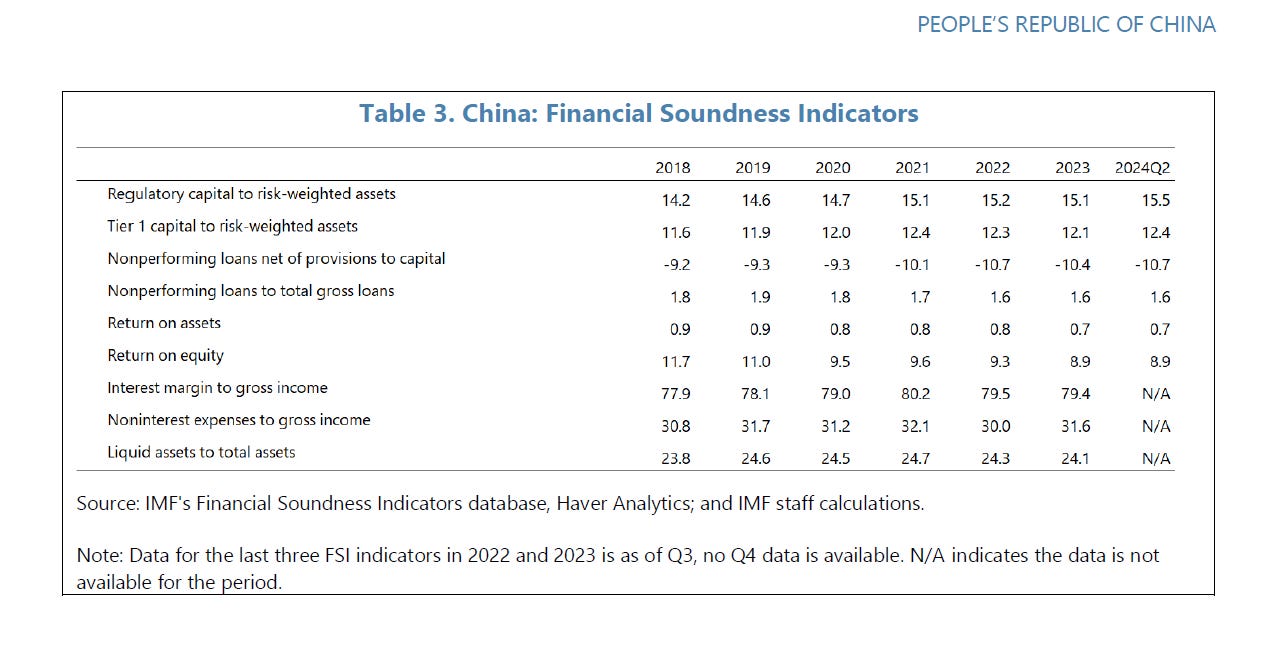

First: Their banking system is fundamentally unsound. Chinese banks are sitting on mountains of non-performing loans that have never been officially recognized. The reported non-performing loan ratio hovers around a remarkably pristine 1%, a figure that defies credibility given the speed and scale of China’s credit expansion.

Second: Their currency is overvalued and has gates. Why else would China maintain strict capital controls limiting citizens to taking just $50,000 USD out of the country annually? It’s not to prevent capital flight; it’s an admission that capital flight is inevitable without such barriers. Their $3.2 trillion in reserves (most of which are illiquid) couldn’t withstand an actual exodus if citizens could freely convert and move their wealth.

Imagine living in a country where your government tells you that you cannot move more than $50,000 of your own money outside its borders each year. What does that tell you about your government’s confidence in the banking system and currency?

Gold becomes the only realistic escape valve. It’s portable wealth that transcends governmental control, and Chinese citizens are rational enough to understand that paying a premium today beats losing everything tomorrow.

The Accounting Trick That Inflates China’s GDP

To understand the scale of China’s problem, we need to examine something few analysts discuss: the fundamental difference in how China calculates GDP versus Western market economies. This insight comes from Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University and one of the most astute observers of the Chinese economy.

The Expense vs. Asset Problem

In financial accounting, there’s a critical distinction between recording expenditures as expenses versus assets. This seemingly technical difference has profound implications for how economic output is measured.

Imagine two identical companies, each spending $50,000 on research and development:

- Company A records this as an immediate expense, reducing its reported profit by $50,000 today.

- Company B records this as an asset, maintaining higher reported profits today, while committing to gradually write down its value over future years through amortization.

In the short term, Company B looks far more profitable and financially stronger. Over the long term, as the asset is amortized, both companies’ financial statements converge. The difference is purely a matter of timing when you acknowledge the cost.

Unproductive Investments and GDP Distortion

This principle becomes explosive when applied to unproductive investments at a national scale.

In the United States and other market economies, when you invest $100 million in a project that ultimately creates only $80 million in real economic value, that $20 million gap must be recognized relatively quickly through:

- Loan defaults

- Corporate bankruptcies

- Debt write-downs

- Bad debt provisions by banks

- Asset impairments

All of these reduce reported economic output. The market forces you to acknowledge reality.

China operates by different rules.

Bad debts in China are rarely formally recognized. Defaults are exceptionally rare—Pettis calls the occasional small defaults “Potemkin defaults,” mere window dressing to suggest the system functions normally. Instead, banks systematically roll over non-performing loans indefinitely, supported by implicit government guarantees and the political sensitivity around acknowledging failed investments.

Government officials and senior Chinese bankers have openly acknowledged this practice. The question isn’t whether it happens, it’s how extensive it is.

The GDP Inflation Mechanism

When bad investments aren’t recognized as losses, they continue appearing as productive assets in national economic accounts. Here’s the critical point: expenditures that would count as expenses (reducing GDP) in Western economies are recorded as assets (maintaining or increasing GDP) in China.

This creates a systematic overstatement of economic output.

Consider a concrete example: China builds a high-speed rail line connecting two cities for $10 billion. In the initial GDP calculation, that $10 billion counts as investment and boosts GDP. But what if the rail line never generates sufficient revenue to justify its cost? What if it operates at a loss indefinitely?

In a market economy, this reality would eventually lead to asset write-downs, loan-loss provisions, and defaults, all of which would reduce GDP. These losses would show up in bank balance sheets, corporate bankruptcies, and revised national accounts.

In China, that rail line remains on the books at close to its original value. The loan financing is rolled over repeatedly. No default occurs. No write-down happens. The GDP contribution remains.

Multiply this pattern across millions of investments, ghost cities, redundant infrastructure, zombie industrial capacity, and unprofitable state enterprises, and you begin to understand the scale of GDP overstatement.

The Debt Mountain Nobody Wants to Acknowledge

The consequences of this accounting approach are catastrophic. Total debt in China has surged to 303% of GDP by the end of 2024. But even this alarming figure doesn’t capture the full picture, as it doesn’t account for the debt accumulated by Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs).

LGFVs are off-balance-sheet entities created by local governments to circumvent borrowing restrictions. Think of them as shadow governmental debt, real obligations that don’t show up in official statistics.

According to the Rhodium group and the latest IMF estimates:

- LGFV debt: $9.8 trillion (47% of China’s GDP)

- 75% of this debt is held by banks.

- Many LGFVs face high indebtedness, illiquidity, and fundamental viability risks.

- IMF staff estimates suggest 39-46% of LGFV debt requires restructuring to restore basic debt servicing capacity.

Read that last point again: up to 46% of $9.8 trillion needs restructuring. That’s potentially $4.5 trillion in debt that cannot be serviced under current terms, equivalent to nearly a quarter of China’s official GDP. This does not include the real estate market, which, depending on various estimates, is between $44 trillion - $60 trillion and whose prices have been falling for the past 5 years. Bear in mind, real estate contributes directly and indirectly between 25% and 30% to China’s GDP and accounts for approximately 70% of household wealth.

And remember: these loans sit primarily on Chinese bank balance sheets, recorded at or near face value, not reflecting their impaired status.

The Impossibly Low NPL Ratio

Chinese banks officially report non-performing loan ratios below 2%.

Let that sink in.

Banks operating in an economy that:

- Has undergone the most rapid credit expansion in human history.

- Maintains extraordinarily low interest rates relative to nominal GDP growth.

- Features a relatively short history of large-scale commercial lending.

- Has seen massive investment in speculative real estate and infrastructure.

...somehow maintain NPL ratios that would be the envy of the most conservative Swiss banks.

This isn’t financial prudence. It’s an economic fantasy.

The Trap: Investment-Driven to Consumer-Led Economy

China is attempting one of the most difficult economic transitions imaginable: shifting from an investment-driven model to a consumer-led economy. For decades, China has achieved growth by building infrastructure, factories, real estate, and more infrastructure. This model has run into diminishing and now negative returns.

The logical next step is to transition to consumer-driven growth, as in developed Western economies. But here’s the trap: making this transition risks exposing all those years of bad investments.

If China shifts focus to consumption and allows unproductive investments to fail, it must recognize those failures. Banks would need to acknowledge bad debts. GDP would contract as write-downs flow through the economy. The illusion of growth would shatter.

But suppose China continues pouring money into investment despite diminishing returns. In that case, it only compounds the problem, creating more unproductive assets that will eventually need to be recognized, making the eventual reckoning even more severe.

This is why Chinese leadership appears paralyzed, oscillating between stimulus and retrenchment. They’re boxed in by years of accounting decisions that prioritized reported growth over economic reality.

You can find more on this dilemma in a previous note: Can China Spend Its Way to Growth?

The Global Context: Trump, Tariffs, and Timing

Now add external pressures to this fragile system. Trump-era tariffs specifically target Chinese exports, the one sector that actually generates real foreign exchange and economic value. As export growth slows or reverses, China’s ability to create genuine economic growth becomes even more constrained.

With the economy slowing, external demand weakening, and enormous amounts of unrecognized debt throughout the banking system, those losses may never be formally acknowledged. Instead, they’ll remain on balance sheets indefinitely, a pool of phantom assets worth far less than stated valuations suggest.

This means China’s actual economic size is significantly smaller than official figures indicate. How much smaller? The honest answer is nobody knows, because the very structure of China’s financial system is designed to obscure this reality.

What the Gold Premium Really Means

Return now to where we started: the Shanghai premium on gold.

Chinese citizens are paying above-market prices for gold, not because they’re sophisticated geopolitical analysts betting on American decline. They’re paying premiums because they’re trapped.

They understand that:

- Their bank deposits sit in an unsound system bloated with bad debt.

- Their currency is overvalued and maintained only through capital controls.

- Their government’s GDP figures are systematically overstated.

- The economic model that created their wealth is broken and cannot continue.

- The transition to a new economic model risks exposing losses that will destroy wealth.

Gold, for them, isn’t an investment thesis about the international monetary system. It’s a life raft.

The Narrative We Should Be Telling

The global financial media has embraced a compelling but incorrect narrative: central banks are buying gold because the dollar’s dominance is ending. This story fits our moment, a time of geopolitical tensions, shifting alliances, and questions about American leadership.

But the data tells a different story. Dollar dominance has, if anything, strengthened in recent years, not in terms of exchange rates, but in terms of what really matters: transaction settlement, access to credit, and the infrastructure of global commerce.

The real story is simultaneously less dramatic and more alarming: the world’s second-largest economy has systematically overstated its size and productivity for years, perhaps decades. It has trapped its citizens in an economic system that prevents them from freely moving their wealth. It faces a debt burden that may be impossible to fully recognize without triggering a crisis. And now, as it attempts to transition to a new economic model, the fundamental fragility of its system becomes impossible to hide.

Chinese citizens buying gold at premiums aren’t revolutionaries betting on a new world order. They’re rational actors responding to an economic reality that many Western analysts refuse to acknowledge: China’s economic miracle may have been substantially smaller than reported, and its future far more constrained than conventional wisdom suggests.

The gold rush isn’t about fears of American decline; it’s about global economic debasement. It’s about the very real, very rational concerns. For Chinese citizens, it’s also about something more: people living inside a financial system that may not be what it appears to be, and who are desperate to secure any store of value that exists outside that system’s control.

That’s the story we should be telling. Because understanding China’s actual economic condition, and the desperate hedging behavior it produces, matters far more for the global economy than another article about a fictional dollar decline (in usage) that the data doesn’t support.