Article by Alan Dunne, CEO of Archive Capital

The Risks Have Not Gone Away

Of course, there may be merit to the bull case in the short term. Inflation is edging lower, the ECB is cutting rates and there’s still no hard evidence of a downturn. Even if we do see a slowdown, markets expect some easing from the Fed later this year. Equities could grind higher. But that doesn’t mean the risks have disappeared.

Valuations for US equities remain elevated. The forward P/E ratio on the S&P 500 is about 22, historically associated with lower-than-average future returns. Even if trade deals are cut, it looks like tariffs are here to stay - likely around 10% - which will be a headwind for the consumer and corporate earnings growth.

Although yields have come off their highs, fiscal concerns continue to lurk in the shadows. The ambitions of DOGE have been scaled back, and Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” could add close to $4 trillion to the deficit over the next decade. All roads seem to point to higher yields - but when?

These macro risks don’t guarantee a downturn, but they make it essential for investors to think critically about how their portfolios are built and where the stress points may lie. In short, this is not a time for complacency. As JFK once said, “the time to mend the roof is when the sun is shining”.

Why Diversification Often Fails

While portfolios appear diversified, with allocations to multiple asset classes, the actual level of resilience is often much weaker.

Multi-asset or diversified growth funds, often marketed as “all-weather”, suffer from the same flaw: a bet on continued sunshine.

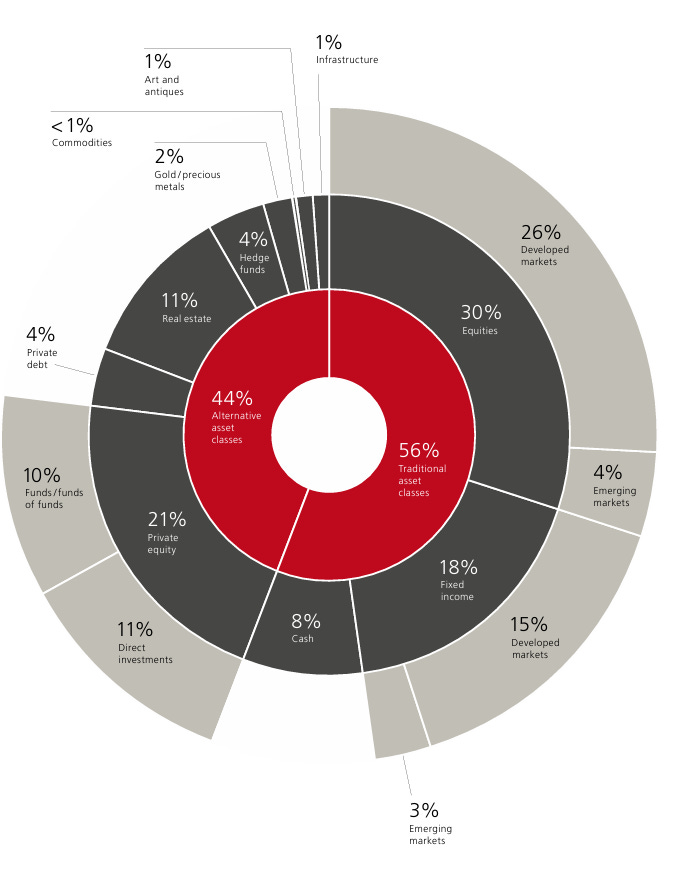

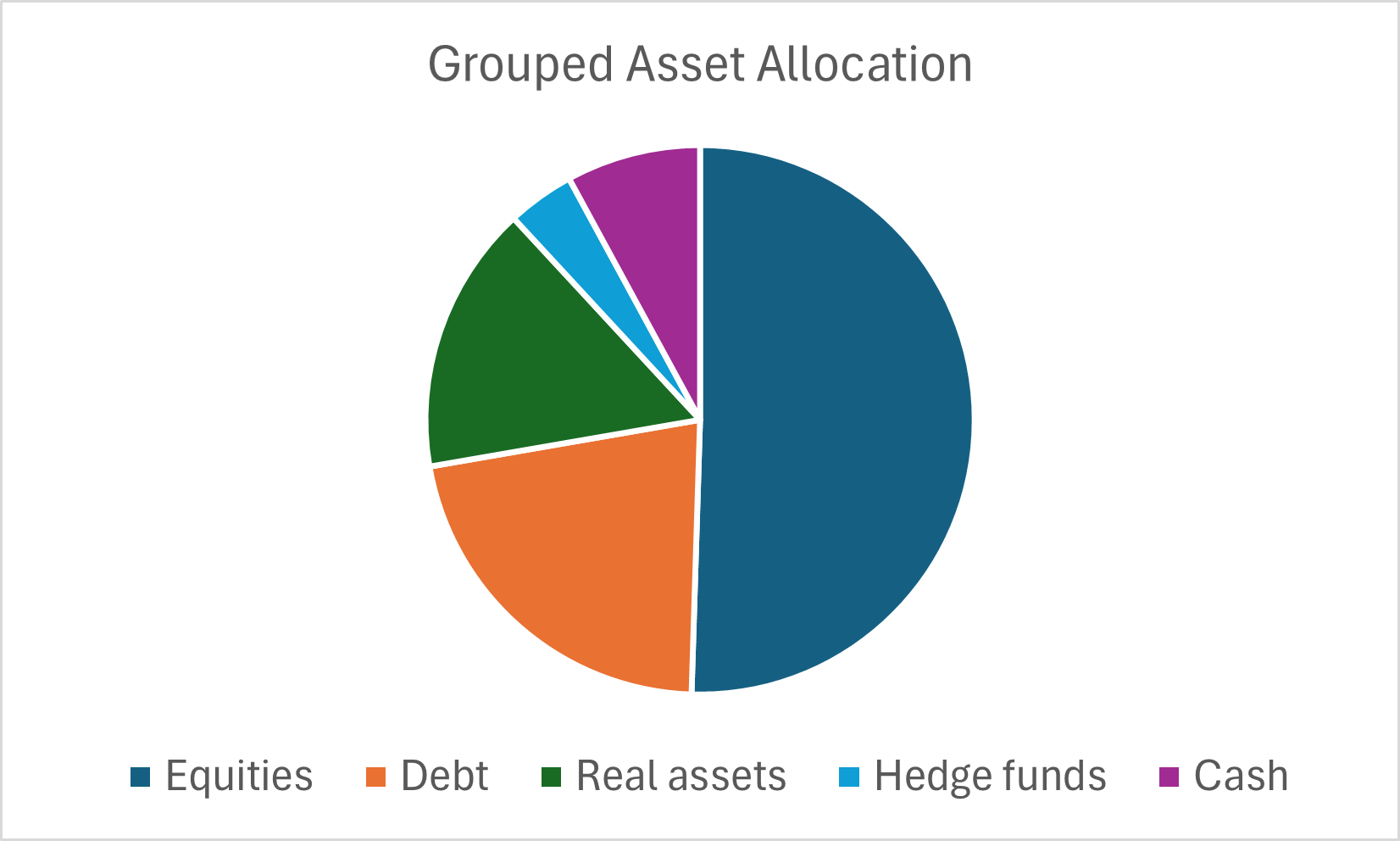

Take the typical family office asset allocation from the recent UBS Global Family Office Report. [1] At a high level it looks quite diversified with allocations to distinct categories from equities to antiques.

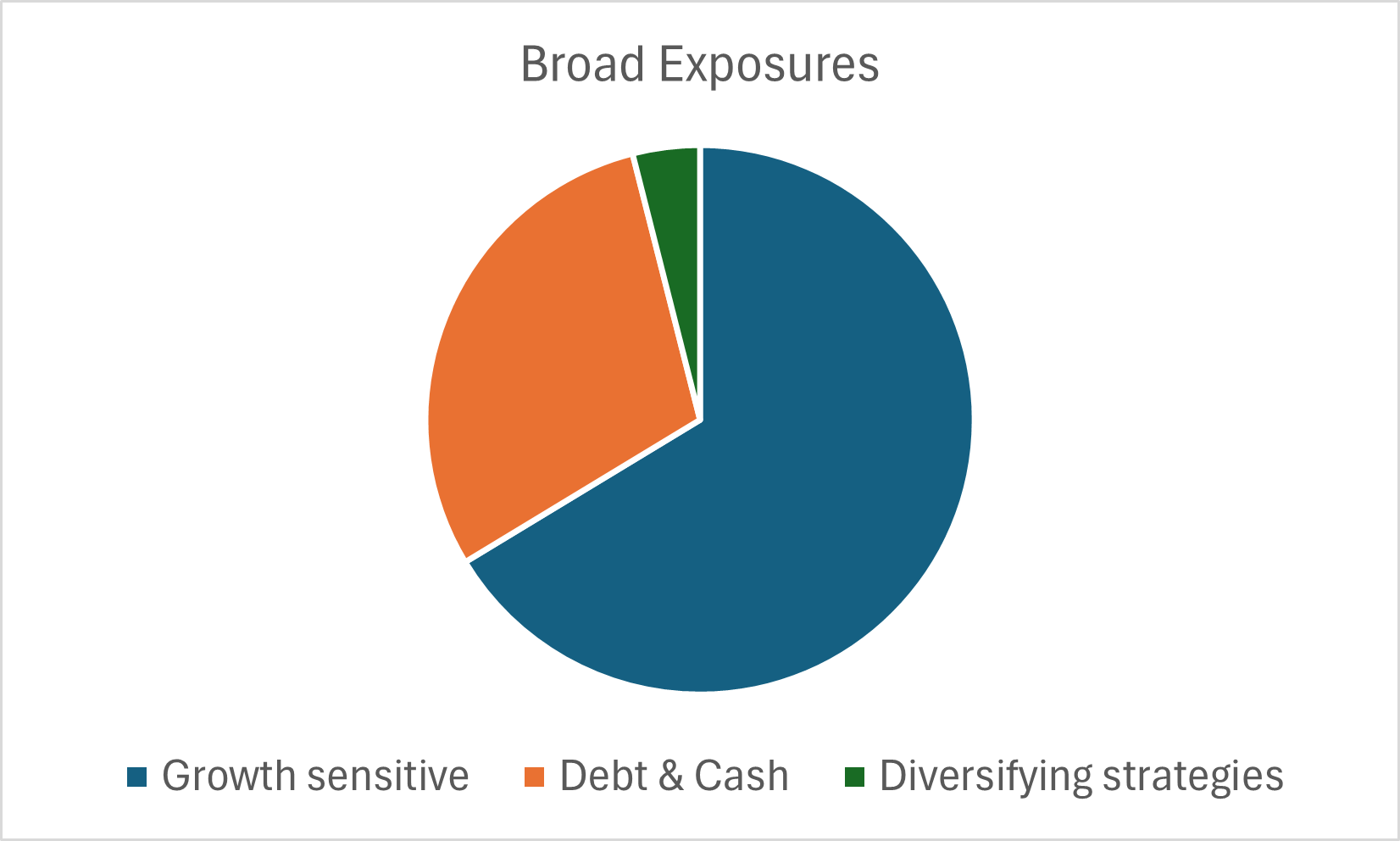

But when you group them into high-level asset classes and broader categories - growth, defence, and diversification - the portfolio looks far less diversified.

And adjusting the allocations for differences in risk would tilt the overall exposure even more to growth.

A wide range of assets - from equities to private equity, private credit, and real estate -tend to perform well when the economy is solid. But in a deep recession, they typically underperform together.

Equally, many strategies - from long-duration bonds to equities- do well when inflation is contained and interest rates are falling. What about a regime of rising inflation?

Weak or contracting growth at a time of inflation - stagflation - is the hardest scenario. While stagflationary risks have flared at times in recent years, we haven’t seen a prolonged stagflationary episode since the 1970s.

Most portfolios are still unprepared for either a severe downturn or a stagflationary environment.

Why Portfolio Construction Still Matters

Sometimes the problem is an absence of truly diversifying strategies. Other times, the right elements are there - but poorly sized or misaligned. Take a 50/50 equity/bond portfolio. On the surface, it looks balanced: equities for growth, bonds for defence. Between 1980 and 2020, long-term government bonds consistently rose when equities sharply fell as central banks came to the rescue cutting rates.

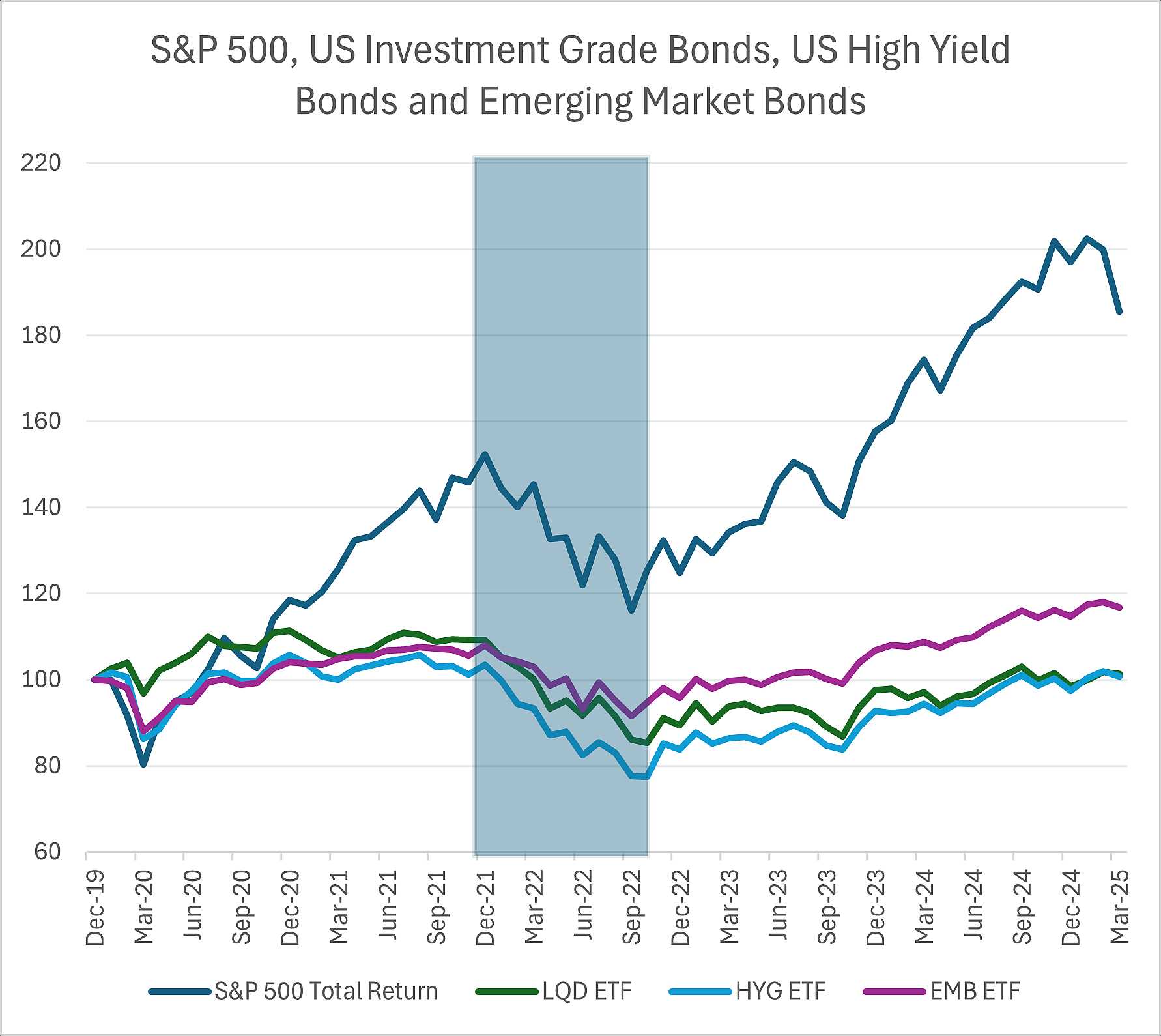

That relationship looks less reliable going forward, particularly if inflation proves sticky or investors require higher yields for holding government bonds. As 2022 showed, equities and bonds can fall together.

Reducing the bond duration might lower interest rate risk but turns the bond allocation into something more like cash: low return and limited ability to generate meaningful return or convexity in times of stress.

Adjusting for risk matters as well. You might see a 50% drawdown in equities, but as bonds are less volatile, even if bonds perform well, they may only offset a fraction of the equity losses.

The composition matters, too. Is the equity sleeve dominated by US growth stocks? For euro-based investors, the risk compounds further if growth underperforms and the dollar weakens.

On the bond side, is the exposure to government debt or to credit?

Investment grade, high yield, or emerging market bonds can offer income in calm markets. However, in periods of acute stress or rising rates (such as March 2020 or 2022), concerns about creditworthiness increase and these assets behave much more like equities - just when you want them to be doing the opposite.

Some investors have embraced alternatives. But calling something “private equity” rather than “public equity” doesn’t fundamentally change its behaviour in a downturn. The fact that you pay more for the private versions – only to get the same downside - adds insult to injury (Editor's note: See also the article “Old promises, new reality - the decline of alternative investments”).

Even those who include truly diversifying strategies - like hedge funds - might not see much impact. The nature of the allocation matters.

If the hedge fund strategy has an inherent equity beta it might not perform well in a more stressed period. Strategies like global macro and trend following have historically fared better in more prolonged equity bear markets.

An allocation of 4% is unlikely to move the needle of the overall portfolio.

If the volatility of the hedge funds is low, the impact on the portfolio may be even less than expected, even for a low allocation like 4%. Paradoxically, higher volatility diversifying strategies can be more risk mitigating for the overall portfolio than lower volatility versions.

It is not just a matter of allocating to hedge funds. It’s about selecting the ones with a reasonable prospect of performing in more stressed conditions and allocating a meaningful amount of the risk budget.

For those looking to build a global macro hedge fund allocation that diversifies, our recent white paper lays out a few key considerations.

The Total Portfolio Approach

Among large institutions there is a growing trend to shift from traditional asset allocation models toward what’s called a “total portfolio approach.” The essence is simple: focus less on asset class names and more on the overall portfolio’s risk exposures. It sounds like common sense, and it is.

The challenge for large institutions is that historically, because of their size, they tended to organise themselves according to the asset class exposure and allow teams to operate independently without really thinking about whether it made sense to allocate the marginal dollar to private equity or hedge funds. That’s now changing.

While the operational challenges are unique to large institutions, the principle - allocating capital to where it adds the most value per unit of risk—applies just as well to private investors: understand what assets you own, how they behave in stress periods, and what role each part plays.

There are ways to construct portfolios that don’t rely on predicting the next crisis - yet can survive when one inevitably comes. It starts with better diversification, more thoughtful sizing, and a clearer understanding of what drives portfolio risk. That typically translates into more meaningful allocations to truly diversifying assets and strategies, like gold, commodities, global macro and trend following.

The use of futures for beta, capital efficiency and greater flexibility can also be helpful, but that’s a story for another post.

Most portfolios I see still reflect the last decade more than the next - but the next is unlikely to resemble the last.